What Is a Sandwich Lease?

REtipster does not provide tax, investment, or financial advice. Always seek the help of a licensed financial professional before taking action.

A Background of the Sandwich Lease

Before describing what a sandwich lease is, it is helpful to understand the terms “lease” and “rent.”

Leasing and renting are often used interchangeably, but they differ in many ways, particularly in duration and changeability.

Lease contracts last longer and are not so easily changed. By contrast, rent contracts are brief in nature and provide more space to make the deal acceptable to the parties involved.

A sandwich lease is a lease agreement, not a rent agreement.

How a Sandwich Lease Works

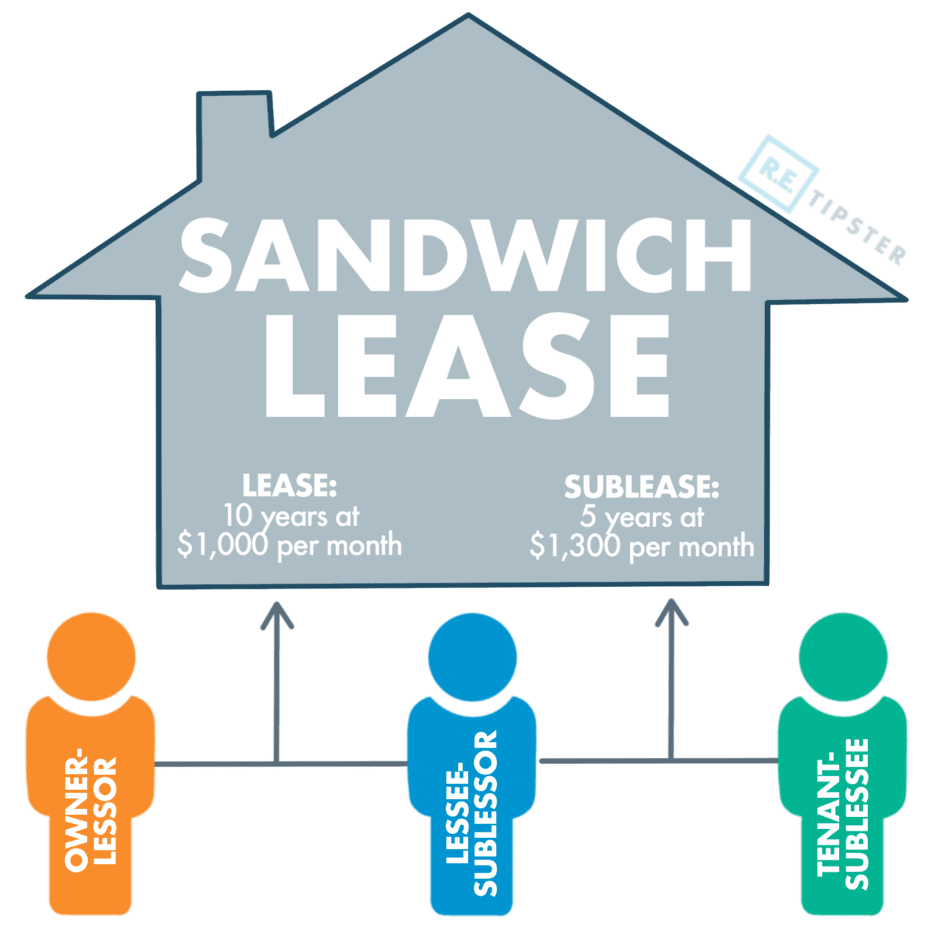

In a sandwich lease, the real estate investor (lessee) rents a house from a home seller or landlord (lessor). In some scenarios, the and sandwich lease is structured with a clear length of time and the lessee remains in place until the term of the lease ends. In a rent-to-own scenario, the lessee has the option to buy the property in a limited time frame at a defined price.

In a sandwich lease, the lease contract permits the original lessee to sublease the property to another party, called the sublessor. In a rent-to-own scenario, this third party is oftentimes a homebuyer who does not qualify for a conventional mortgage[2] but intends to purchase the house in the future.

In this arrangement, the lessee agrees to a monthly lease amount and pays the lessor a one-time option fee to initiate the deal. In a rent-to-own scenario, the specified portion of the rent and the upfront option fee can be applied as a down payment for the purchase price[3].

Meanwhile, the sublessee pays rent and the option fee to the original lessee, which is generally higher than what the lessee is paying to the lessor. The lessee uses this cash to pay for their original contract with the lessor and pockets the difference as profit.

In other words, the lessee neither occupies the property at any point nor pays from out of their own pocket. Instead, they look for a buyer who wants to be a homeowner, charge them a higher price than what the lessor stipulated, and use the money from this third party to pay for their obligations to the lessor. The lessee acquires the cash flow generated from the spread between the original rent and the sublessee’s rent.

With the sandwich lease, the lessee has the potential to earn three types of profit from the deal by:

- Raising the rent.

- Charging a larger option fee.

- In a rent-to-own scenario, selling the property when its equity[4] has grown.

In turn, the sublessee enjoys the exclusive right to lease and possibly buy the house within a specified period at a fixed price without the obligation to commit to the purchase[5].

Why Is It Called a Sandwich Lease?

The word “sandwich” is a perfect metaphor for this lease agreement[6] because the lessor and the sublessor represent the two pieces of bread, and the lessee is the meat in that sandwich. The analogy is also apt to illustrate how the lessee, the investor, gets the meat of the deal.

The lessee can turn a profit whether or not the end buyer ultimately makes the purchase by simply finding the rent-to-own home seller first. In principle, the lessee can sell a house for a profit without owning it.

That said, this strategy is not without risk[7], as explained below.

What Is an Example of a Sandwich Lease?

To further demonstrate how a sandwich lease works, here is a hypothetical scenario:

Suppose a real estate investor finds a homeowner who has to move out as soon as possible but cannot sell the house quickly or use an agent. This investor can make an offer and explicitly pitch a sandwich lease scenario. The homeowner agrees and signs the contract, which becomes the master lease[8].

Both parties agree that the real estate investor (lessee) will pay $2,300 per month in rent to the seller for four years and an upfront option fee of $5,000. The contract says that 20% of the rent ($460 per month) will go toward the property’s agreed-upon purchase price of $200,000. The contract also states that the real estate investor can exercise their option to buy the property before the master lease expires, if and when they choose.

To turn a profit from this deal, the real estate investor (lessee) must find a third-party sublessee/buyer, who is interested in a rent-to-own house. Upon finding this third-party sublessee/buyer, the real estate investor (lessee) presents a lease-option deal for three and a half years for the subject property.

The third-party buyer agrees and signs a similar contract to the lessee’s, except that the rent, the upfront option fee, and the property’s purchase price are all higher: $3,000 monthly in rent, a $6,000 option fee, and a house price tag of $265,000. 20% of the rent ($600 per month) also goes to the purchase price.

Once the three and half years (42 months) are up and if the third-party sublessee/buyer follows through on the purchase, their figures would look as follows:

- Third-party buyer pays the real estate investor $233,800 (net purchase price after deducting the accumulated rent of $25,200 and the option fee).

- Real estate investor pays the seller $175,680 at closing after deducting $19,320 from rent and the option fee directly toward the prearranged purchase price.

- Real estate investor still gets $200,000, the original purchase price.

The spread between the net purchase prices is $58,120. This amount is the lessee’s profit from the deal.

What Happens When a Sandwich Lease Ends?

The sandwich lease ends once the sublessee exercises their option to purchase the property. This could be done by taking out a home loan or directly borrowing from the lessor or lessee through a seller financing arrangement[9]. If the sublessee does not choose to buy before the sublease term is up, the sublessee loses the portion of the rent reserved for the property purchase and the option fee they paid to the lessee.

If the deal with the sublessee falls through, the lessee can step in and buy the rent-to-own home out of their own pocket. But if the lessee walks away and lets the deal expire, the lessor cannot legally force the other party to complete the sale. Despite missing out on a hefty profit, the lessor gets to keep the property together with the lessee’s additional rent payment and one-off option fee.

The sublessee is not forced to buy a house. The lessee receives profits without borrowing capital to own an unwanted property. And the lessor keeps an asset and the option fee plus regular rental income[10] throughout the duration of the sandwich lease. In the end, everybody wins.

However, the ending might be different in cases when the master lease expires before the sublease agreement does.

In this scenario, the sublessee can just wait out the contract in hopes of negotiating directly with the lessor. The two parties may find it more rewarding to do so and totally exclude the lessee from the deal.

The lessee may legally challenge any attempt to cut them out, but getting the deal strategically correct in the first place is much easier than suing the other parties.

Takeaways

- A sandwich lease is an agreement that, depending on how it is structured, may give the lessee the option, but not the obligation, to buy the rent-to-own house and simultaneously sublease it to another party.

- The sandwich lease is called such to describe the real estate investor’s position in the middle of the leasing relationship involving the lessor, lessee, and sublessee.

- The sandwich lease ends when the term expires or when the lessee decides to purchase in a rent-to-own scenario. If the lessee purchases the home, it ideally happens after the sublessee becomes mortgage-ready and finances the house. Otherwise, the lease will end when the contract expires and the lessee walks away.

Sources

- Keilig, M. (2021.) How Does Rent to Own Work? Plus the Pros and Cons! Better Homes and Gardens Real Estate HomeCity. Retrieved from https://www.homecity.com/blog/how-does-rent-to-own-work/

- Keeping Current Matters. (2019.) Do 46 Million Millennials Know They Are Mortgage Ready? Retrieved from https://www.keepingcurrentmatters.com/2019/03/20/do-46-million-millennials-know-they-are-mortgage-ready/

- Cook, S. (2016.) The 20% fallacy: Why you do NOT need 20% down — or do you? Inman. Retrieved from https://www.inman.com/2016/07/11/the-20-fallacy-why-you-do-not-need-20-down-or-do-you/

- Pritchard, J. (2021.) What Is Home Equity? The Balance. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-home-equity-315663

- Braverman, B. (2019.) 6 questions to ask about a lease-option to buy a home. Bankrate. Retrieved from https://www.bankrate.com/real-estate/questions-to-ask-about-a-lease-to-buy-option/

- Kimmons, J. (2019.) Elements of Real Estate Lease Agreements. The Balance Small Business. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancesmb.com/elements-of-real-estate-lease-agreements-2866927

- RLT Finance. (n.d.) Benefits and Risks of Sandwich Lease Options. Retrieved from https://roadlesstraveledfinance.com/benefits-and-risks-of-sandwich-lease-options/

- Hamed, E. (2020.) What Is a Master Lease in Real Estate. Mashvisor. Retrieved from https://www.mashvisor.com/blog/what-is-master-lease-real-estate/

- Ceizyk, D. (2021.) Rent-to-Own Homes: What You Need to Know. LendingTree. Retrieved from https://www.lendingtree.com/home/mortgage/rent-to-own-homes-guide/

- Caplinger, D., Frankel, M., & Wathen, J. (2018.) 3 Things You Should Know About Rental Income. The Motley Fool. Retrieved from https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2016/01/02/3-things-you-should-know-about-rental-income.aspx