What Is a Trust?

REtipster does not provide legal advice. The information in this article can be impacted by many unique variables. Always consult with a qualified legal professional before taking action.

How Trusts Work

In a trust, the trustor (which may include the asset owner and their attorney/s) decides how their assets are transferred to the beneficiary under the guidance of a trustee. The latter’s job is to manage, dispense, and distribute the assets based on the terms and purpose of the trust.

Trusts are useful legal vehicles that can hold many types of assets, including real estate. They also guarantee that the assets are managed to do the most good for its beneficiary. An example is establishing a trust for a beneficiary that could not carry out the appropriate decisions to manage the trustor’s assets. A trust literally entrusts the care of these assets to a trustee, so the beneficiary enjoys their benefits without having to manage them.

Trusts are nothing new, though. Trust-like entities have existed as early as classical Greece but were only fully established during the Middle Ages[1]. Recently, however, trusts have become objects of scorn or ridicule because they are often associated with people who owe their wealth to a trust fund—the so-called “trust fund babies.”

Trust vs. Will

Both trusts and wills are tools for estate planning. While the United States Estate and Gift Tax laws[2] protect wealth passed on to a spouse from estate tax or gift liabilities, the same cannot be said about wealth passed on to heirs. This is where a will, a trust, or both enter the picture.

In a will, the original owner of the wealth, assets, or objects can choose the direct beneficiaries who will be named on a will. The will becomes active only when the original owner dies.

A will must also go through probate, a lengthy legal process in which the authorized court administrator examines the will for its validity. In many cases, family members contest the will, which can make the process more difficult.

On the other hand, a trust offers more control, particularly if it is designed as a living trust. The trustor may change the assets in the trust, the trustee, the beneficiary, or the terms of the trust while they are still alive[3]. In addition, the trust becomes active on the day it is created.

A trust also bypasses probate. It cannot be contested, either. However, a trust is more expensive to set up than a will; it takes longer to create and has to be funded and actively managed[4].

Whichever works better in estate planning depends on the asset owner’s needs, financial capability, and other considerations.

Why Are Trusts Made?

Typically, there are several reasons owners create a trust. A trust can avoid taxes and probate on the assets and protect them from creditors. The trust can also help reduce paperwork and save time. Most often, trusts are made for estate planning.

When the owner of an asset dies without specifying an estate plan, their assets go to an “intestate succession[5].” This is where the state decides how to distribute their assets to their surviving relatives, generally in this order: a surviving spouse, then children, then closest relatives, then distant relatives.

Obviously, dying intestate will mean that the asset owner will not have control over which heirs get a share of the assets. As such, estate planning covers how asset owners can use a trust or a will to direct which of their heirs get a share of the assets as they deem fit.

Still, even in a trust, there is no guarantee that the beneficiary could wield and/or manage the assets as the trustor originally envisioned. In this case, a trustor may choose a trustee to oversee and manage these assets on behalf of the beneficiary—acting as the asset manager while the beneficiary receives all its benefits.

In other words, if there is no trust created to protect these assets, the assets may be at risk.

A person establishing their will can also ensure the privacy of the will through a trust[6]. In some jurisdictions, the terms of a will may become public. If a trust is set up instead, the trustor can ensure the privacy of their will.

Common Entities Involved in a Trust

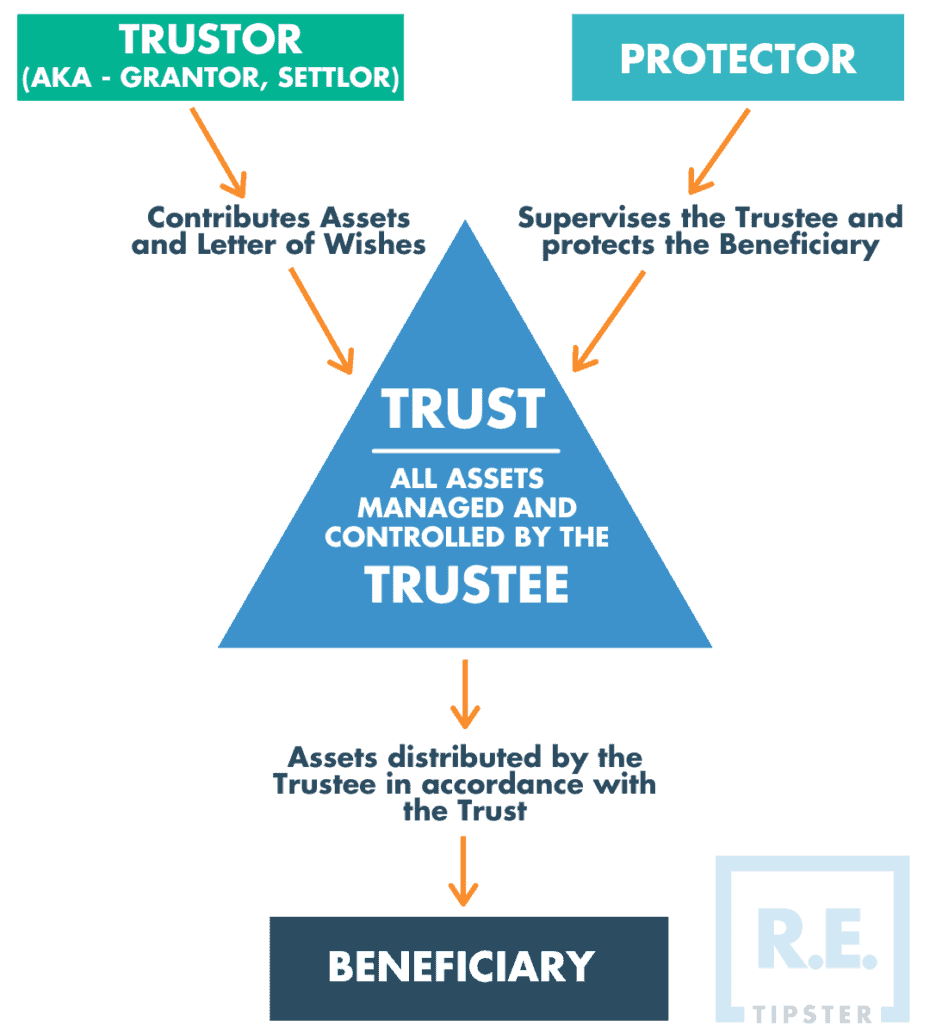

There are three main entities involved in a trust, plus an optional entity called a protector. The following is a description of their duties and responsibilities.

Trustor

A trustor is a person, persons, or organization that establishes a trust. If the trustor makes a settlement, particularly of a property, the trustor is also called a settlor or a grantor.

Trustee

A person or persons designated by a trust to hold title to and manage the property or assets is called a trustee. The trustee has a fiduciary responsibility, which means they are legally and ethically bound to protect the property or assets of the trustor and act in the best interests of the trust’s beneficiary. They can also be held personally liable for any breach of this duty.

A trustor must make sure, to the best of their ability, to choose a trustee they can truly trust. However, they must be even more certain that the protector is trustworthy—hence the name “trust.”

Protector

A protector is someone who watches over the trustee. The protector has the power to terminate or fire the trustee if the trustee is not acting according to the terms of the trust. This role, however, is not always required in a trust.

If a protector removes the original trustee, the original trust document is referenced so a successor trustee can be appointed. In many cases, a protector has additional powers, including choosing and appointing a successor trustee after firing the original one.

Unless the trust specifies that they are prohibited from doing so, a protector can assign themselves as a trustee to take control of the assets[8].

Beneficiary

The beneficiary of a trust is the entity or person for whom the trustor establishes the trust. For example, the beneficiary of a trust set up by a parent is often their children. The beneficiary can also be another person or a charitable organization. There can also be more than one beneficiary.

It is legal in some areas—and quite common, in fact—for a beneficiary to be a trustee at the same time[7].

Types of Trusts

There are many types of trust, but most of them fall under either a revocable or an irrevocable trust. Other types are discussed and compared below.

Revocable vs. Irrevocable Trust

A revocable trust is a type of trust that the trustor can either change or terminate during the trustor’s lifetime. In this logic, only living trusts can be either revocable or irrevocable.

The trustor cannot change irrevocable trusts once established. Some trusts also become irrevocable only after the death of the trustor, while some types, like testamentary trusts, can only be irrevocable.

In many cases, an irrevocable trust is better. One major advantage is that estate taxes can be minimized or completely avoided because the trust is unalterable, which means it continues to protect assets permanently removed from the possession of the trustor[9].

Living vs. Testamentary Trust

Also called an inter-vivos trust, a living trust ensures the use of the assets for the trustor’s benefit during their lifetime. Once the trustor ceases to live, the assets are transferred to the named beneficiaries in the trust. The trustee directs the trust to ensure the proper management and transfer of the assets in the trust.

On the other hand, a testamentary trust is a legal document specifying how the trustor’s assets should be designated at the time of their death. A testamentary trust is also called a will trust. It is an irrevocable type of trust[10].

Funded vs. Unfunded Trust

When a trust is funded, the trustor, during their lifetime, puts assets into the trust. If a trust is unfunded, it is only the trust agreement; there is no funding. If the trustor dies, the trust can remain unfunded or it can become funded, depending on the setup.

An unfunded trust does not offer the protection that a funded trust offers, so an unfunded trust exposes the assets to the perils the trust is designed to protect them from in the first place[11].

Land Trust

A land trust is also an estate planning tool, but it is specific to real estate[12]. It is a living trust, which means a trustor can establish a land trust and benefit from it even during their lifetime to manage the ownership of their property or properties. The trustor can specify the conditions and terms of a land trust, so a land trust is often unique to the needs of the trustor and the type of real property they own.

A land trust is also often revocable.

Some types of assets that are often protected by and managed with a land trust include:

- Houses

- Commercial buildings

- Land

- Property notes

- Mortgages

Takeaways

A trust is a legal vehicle enabling the trustor to transfer their assets for the use of a beneficiary, while appointing a trustee to oversee and manage the terms of the trust. It is often used in estate planning, alongside or as an alternative to a will. However, unlike a will, trusts are established to avoid or bypass certain processes that a will is subject to, such as taxes and probate.

There are many types of trusts, but they often fall under a living trust (a trust from which the asset owner can benefit while they are alive) or testamentary trust (a trust that protects the assets and ensures their proper distribution to beneficiaries upon the death of the trustor). Trusts can also be revocable (the trustor can change or terminate the trust while the trustor is alive) or irrevocable (the trustor cannot change or terminate the trust). Revocable trusts become irrevocable upon the trustor’s demise.

Sources

- Lexon Incorporations. (n.d.) History of the Trust. Retrieved from https://lexcorp.com/en/trust/history/

- Internal Revenue Service. (n.d.) Frequently Asked Questions on Gift Taxes. Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/frequently-asked-questions-on-gift-taxes

- Wong, B. (2021.) What Is a Living Trust? LegalZoom. Retrieved from https://www.legalzoom.com/articles/what-is-a-living-trust

- Jarrell, M. (2021.) Will vs. Trust: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/051315/will-vs-trust-difference-between-two.asp

- FindLaw. (2021.) Understanding Intestacy: If You Die Without an Estate Plan. Retrieved from https://www.findlaw.com/estate/planning-an-estate/understanding-intestacy-if-you-die-without-an-estate-plan.html

- Fordham, D. (n.d.) Confidentiality and Estate Planning. Law Office of Dennis A. Fordham. Retrieved from https://dennisfordhamlaw.com/articles/2confidentiality-09-30-09/

- Nolo.com. (n.d.) Advice to Trustees: Get Along With Beneficiaries. Retrieved from https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/advice-trustees-get-along-with-32451.html

- Adkisson, J. (2012.) Trust Protectors — What They Are and Why Probably Every Trust Should Have One. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jayadkisson/2012/08/25/trust-protectors-what-they-are-and-why-probably-every-trust-should-have-one/?sh=460b4db45abc.

- Nawrocki, T. (2012.) Revocable Trusts vs. Irrevocable Trusts: Which Trust Is Right for Your Clients? ThinkAdvisor. Retrieved from https://www.thinkadvisor.com/2013/08/09/revocable-vs-irrevocable-which-trust-is-right-for-your-client/

- Wolters Kluwer (2020.) Types of Trust: Revocable, Irrevocable, Living, and Testamentary. Retrieved from https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/types-of-trusts-revocable-irrevocable-living-and-testamentary

- Garber, J. (2021.) What Is Funding a Trust? The Balance. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/what-does-it-mean-to-fund-a-trust-3505280

- Lake, R. (2020.) What Is a Land Trust and Who Needs One? SmartAsset. Retrieved from https://smartasset.com/financial-advisor/land-trust