What Is Straight-Line Depreciation?

REtipster does not provide tax, investment, or financial advice. Always seek the help of a licensed financial professional before taking action.

How Depreciation Works

Depreciation is the loss or decline in an asset’s value over time.

There are various ways to calculate depreciation, but the simplest is by using the straight-line basis. It assumes a consistent loss of value over a specified period.

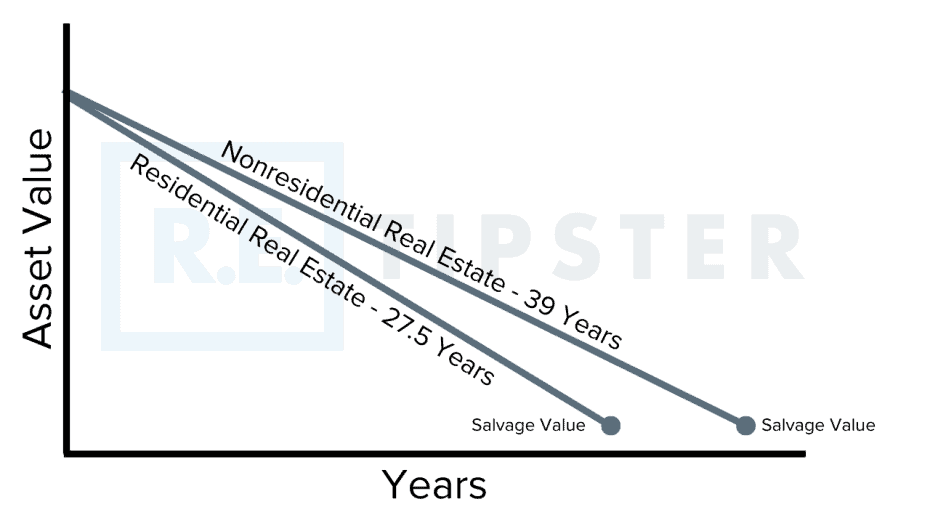

The straight line is literal in this sense, as when graphing the asset’s value over time, it will appear as a straight line.

How Depreciation Happens in Real Estate

One of the great things about real estate investing is that it offers a lot of significant tax advantages that other investments don’t.

Like it or not, there are A LOT of ongoing expenses that will impact your financials when you own a long-term investment property.

Some of these expenses are very big, very real and they hit your bank account on the regular.

Others are “phantom expenses” that don’t have a direct or immediate negative impact on your cash balance. These expenses are paper losses that reduce your taxable income – which ultimately means, you get to keep more of your money and pay less to the IRS each year.

One prime example is depreciation.

Depreciation is an expense that the IRS allows real estate investors to write off each year to account for the natural wear-and-tear that occurs to the physical improvements at each property.

Everything wears out and needs to be replaced eventually, and the depreciation write-off is the government’s way of acknowledging this, even when a direct repair or replacement cost isn’t incurred each year.

Since this depreciation expense effectively bumps up the investor’s cash flow each year (reducing the amount they owe in taxes), Robert Kiyosaki refers to it as “phantom cash flow“:

Depreciation (phantom cash flow): This appears as an expense when it’s really income that comes from a tax break. This confuses many people who are new to investing in real estate; it’s essentially income you don’t see.

But how exactly does depreciation work? How much of the original purchase price can you write-off each year and how many years can you spread out the expense?

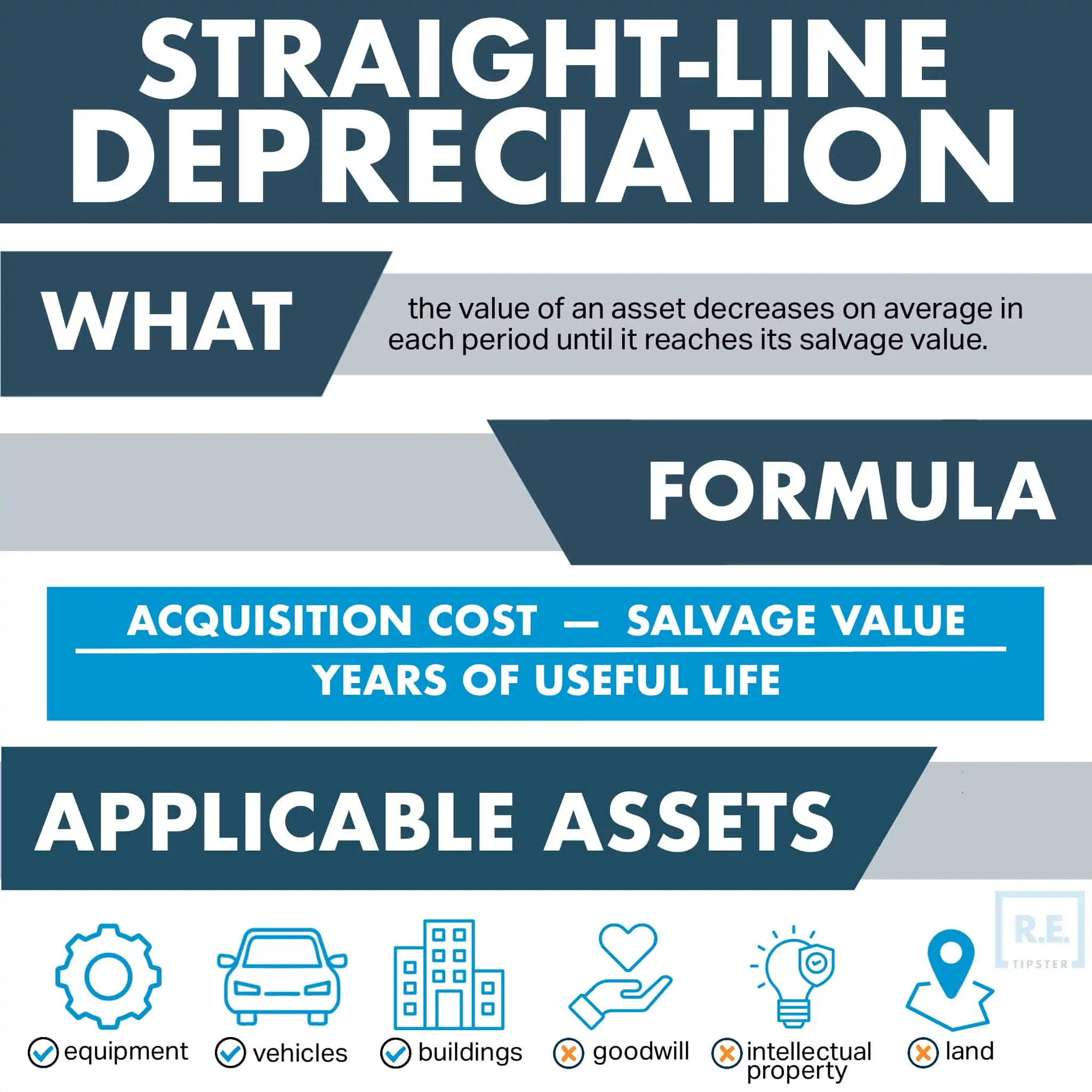

What is Straight-Line Depreciation?

There is more than one way to calculate depreciation.

The IRS has several specific formulas that need to be followed when applying depreciation expense to your investment properties… but the simplest and most common method that applies to most properties is called straight-line depreciation.

As the name suggests, straight-line depreciation requires that you spread out the original cost of the property evenly, over a set period of time.

At the time of this writing, residential investment properties can be depreciated over 27.5 years at equal intervals each year and nonresidential properties can be depreciated over 39-years, at equal intervals each year (don’t ask me where the IRS came up with those numbers).

If you’re a visual learner, it looks like this:

Equal intervals are the key to straight-line depreciation.

Every year, you write down the same amount of depreciation as an expense on your tax return, and this is done for a preset number of years. As explained above, the number of years varies based on the type of asset, and how long it’s expected to last.

The calculator below can help you compute for straight-line depreciation without needing complicated formulas.

Straight-Line Depreciation Calculator

Residential vs. Nonresidential: What's the Difference?

Depreciating a property over 27.5 years (residential) will obviously give you a larger annual write-off than if you depreciate it over 39 years (nonresidential)… so how exactly does the IRS classify a property on either side?

This massive publication explains it in painstaking detail, but these two excerpts are what you’ll want to pay attention to:

Residential rental property. This is any building or structure, such as a rental home (including a mobile home), if 80% or more of its gross rental income for the tax year is from dwelling units. A dwelling unit is a house or apartment used to provide living accommodations in a building or structure. It does not include a unit in a hotel, motel, or other establishment where more than half the units are used on a transient basis. If you occupy any part of the building or structure for personal use, its gross rental income includes the fair rental value of the part you occupy.

Nonresidential real property. This is section 1250 property, such as an office building, store, or warehouse, that is neither residential rental property nor property with a class life of less than 27.5 years.

In other words, if you own an investment property and 80% or more of its annual gross rental income is coming from dwelling units (i.e. – people actually live there, including apartments, duplexes, etc) then it’s considered residential.

A building with both residential and commercial (i.e. – apartments on top and storefront on the bottom) needs to pass the 80% test in order to be depreciated as residential property, otherwise, it is classified as non-residential (you don’t prorate the costs of the property).

RELATED: The Best Profits in Real Estate – Are in the Losses

The Straight-Line Depreciation Formula

The good news is that straight-line depreciation is extremely simple to calculate.

You need to know three numbers to do it:

- The Acquisition Cost

- The Salvage Value (or Land Value)

- The Useful Life or Depreciation Period

Acquisition Cost

This is normally the purchase price, plus related acquisition costs like sales taxes, shipping, or installation fees. In the case of real estate, some closing costs are depreciable, but not all. Your accountant or tax software can help guide you through which closing costs are immediately deductible versus depreciable.

Salvage Value

When the item reaches the end of its useful life, it usually still has some scrap value. For example, when a car is no longer drivable, the parts retain some value for scrap. In real estate, even when a building collapses, burns down or otherwise offers no more value, the land value remains, so the land value serves as the salvage value.

Who determines the salvage value (i.e. – land value) in this process?

In some ways, it’s a bit of a “gray area”. For smaller residential properties, some accountants will look at the assessor website to see how they valued the land, real estate, and land improvements and compare all that to the purchase price of the property and make an educated guess to determine basis in the property.

For commercial property, there is usually a bit more detail in what is considered, including blueprints, maps of the property, pictures of the property (most of which will be included in a professional appraisal).

Useful Life

As outlined above, the IRS specifies a depreciation lifespan for various business and investment expenses. But even when you’re using depreciation for your own accounting purposes rather than your tax return, the premise is the same. How long do you expect the item to remain usable?

To make the calculation, you subtract the salvage value (i.e. – land value) from the acquisition cost, and then divide that number over the years of useful life (27.5 years for residential, 39 years for nonresidential).

Put as an equation, it looks like this:

Examples of Straight-Line Depreciation

Say you buy a computer for business use. You spend $1,550 on it and figure you can sell it for $50 to a computer repair shop to use for parts after five years. And as it happens, five years is the IRS depreciation period for computers.

You subtract the $50 scrap value from the $1,550 purchase price to reach $1,500 in depreciable value. Then, you divide $1,500 by five years, to reach an annual depreciation of $300.

Every year for the next five years, you can deduct $300 for that computer. It’s that simple.

Switching to real estate, imagine you buy a rental property for $150,000. The assessor puts the land value at $50,000, and the improvement (the building) value at $100,000.

So, you divide the $100,000 building value by 27.5 years, for an annual depreciation of $3,636.36. That’s how much you can deduct each year for the next 27.5 years for depreciation, for that particular property.

Not exactly advanced calculus, right?

Why is Depreciation Important?

There are two uses for depreciation: tax preparation and internal accounting.

For tax preparation purposes, you need to know exactly what you can and can’t deduct for depreciation. Beyond keeping you out of prison and audit nightmares, understanding depreciation will help you forecast your taxable income and deductions.

Taxes aside, you also need to track your assets’ value over time for your own books. What the IRS lists as the usable lifespan for your business equipment may not be an accurate reflection of reality in your business. And in real estate, your buildings almost certainly won’t be worthless after 27.5 years.

In some cases, businesses even use different methods of depreciation for their taxes versus their internal books. It’s one more reason why many businesses keep two sets of books: tax-adjusted basis books and book-adjusted basis books.

Depreciation Recapture

If depreciation sounds completely upside when it comes to taxes, keep in mind that Uncle Sam always gets the last laugh.

When you deduct for depreciation, but then sell your property for more than the scrap value (or land value) that you set, guess what happens? You have to pay the IRS back.

Depreciation recapture involves paying taxes on gains you had previously deducted for in the form of depreciation. You pay taxes on gains over your adjusted cost basis.

Returning to the computer example, you planned on a scrap value of $50 after five years. But instead, imagine you sell the computer for $550 after five years. You had deducted $1,500 for depreciation over five years, but your actual loss was only $1,000.

While your adjusted cost basis after claiming all that depreciation was $50, you sold the computer for $550. You owe taxes on that additional $500.

And not at the lower capital gains tax rate, either. You owe taxes at your normal income tax rate.

Depreciation Recapture with Rental Properties

The most common scenario for depreciation recapture, at least for real estate investors, occurs with rental properties.

Let’s revisit the rental property example above. You buy a property for $150,000 and depreciate $3,636.36/year, based on the $100,000 building value.

Imagine you own the property for 11 years, then decide to sell. You sell the property for $250,000 and pop a champagne cork to celebrate your huge payday.

Uncle Sam is going to celebrate too, after collecting taxes from you. Here’s how your taxes on that property look.

After 11 years of deducting $3,636.36/year for depreciation, you saved taxes on $40K worth of income (11 x $3,636.36 = $40,000). Your adjusted cost basis for the property is now $110,000, not $150,000.

So, you’re going to pay taxes on $140,000 worth of gains: the $250,000 sales price minus your $110,000 adjusted cost basis.

With me so far? Good, because it gets a little more complicated yet.

You owe taxes on $140,000 of gains, but that $140,000 is not all taxed the same. On the $40,000 of depreciation recapture, you owe normal income taxes. On the $100,000 difference between your original purchase price and your eventual sales price, you owe taxes at the lower capital gains rate.

That’s the end of the math challenges. It’s smoother sailing from here.

Common Depreciation Quirks

Now that you understand the fundamentals of straight-line depreciation, it’s time to throw in a few more real-life curveballs.

Prorating Depreciation

First of all, real estate investors rarely buy properties on January 1. This means they can’t depreciate the property for the entire year, in the year when they purchase.

When you buy a property mid-year, you have to prorate the depreciation based on the number of days you actually owned the property in that year. It works similarly to prorating rent.

Converting a Primary Residence

Another source of confusion for many property owners arises when converting a primary residence to a rental property. You move out, but instead of selling, you keep the property as a rental – but what’s your cost basis?

In that case, it’s typically the property’s value at the time of its conversion to a rental property. If you get too aggressive on estimating the building value and deducting for depreciation, remember that you’ll owe taxes on depreciation recapture when it comes time to sell!

Finally, inherited properties raise a whole new question of cost basis. If you inherit a rental property, typically you’ll use the fair market value of the property at the time of your benefactor’s death as the cost basis for depreciation.

Determining Salvage Value

When you acquire a property, you need to analyze the costs to determine what and how each component should be or not be depreciated. As mentioned earlier, typically you have to allocate some portion to land (which can’t be depreciated). However, if you acquired a condo unit, oftentimes this property type doesn’t have any land value associated with it.

RELATED: How to Calculate Land Value for Taxes and Depreciation

In addition, you may also be acquiring other personal property in the acquisition which could be depreciated over a shorter life than the typical 27.5/39 years for residential/commercial property.

For example, did you acquire appliances/carpet/furniture (possible 5.0/7.0 life assets)? Did you acquire sidewalks, driveways, fences, landscaping, wells, sprinkling systems, etc which would be land improvements (15-year life)? A Cost Segregation study should be completed if necessary. See the information/reading material in the attachments.

Can Other Real Estate Assets Be Depreciated?

Beyond depreciating rental properties, what do real estate investors need to know about depreciation?

First, remember that land is not depreciable. If you invest in raw land, you can’t depreciate it, but you can depreciate some non-building improvements such as landscaping.

Rental investors should also understand that new appliances, such as refrigerators and ovens, must be depreciated separately from the property itself. When you buy a new appliance for one of your units, you can depreciate that single item over five years for tax purposes.

The IRS classifies capital improvements, however, as extending the usable lifespan of the building. Therefore, they must be depreciated over a longer period, commonly 15 years. Property updates such as a new roof fall under the category of capital improvements.

Finally, commercial real estate investors must depreciate their properties over a longer period: 39 years.

Other Methods of Depreciation

Straight-line depreciation assumes that the asset declines by the same amount every year. That makes it simple to calculate, but not always the most accurate way to depreciate an asset.

So what are some other options, when depreciating assets?

Double Declining Balance Depreciation

Some assets, like computer equipment and vehicles, lose value faster in the first few years of use than they do in later years. The difference in value between a never-owned car and a one-year-old car is vast, while the difference between a six-year-old car and a seven-year-old car is much narrower.

For these assets, owners often use the double-declining balance depreciation method. It allows for accelerated depreciation at first, followed by slowing losses in value.

Unfortunately, it’s also far more complicated to calculate. But as a real estate investor, you probably won’t need to use it often, since real estate is depreciated using straight-line depreciation.

Your accountant or tax preparation software can help you run the numbers if you depreciate certain business-related assets using the double-declining balance method.

Units-of-Production Depreciation

Some assets depreciate at faster or slower rates based on usage. For example, manufacturing machinery often loses value based on how many units it produces – hence the name.

When usage is the key factor in calculating depreciation, use the units-of-production method. Instead of being based on a life span in years, its life span is measured by the total units you can expect it to produce.

This method typically doesn’t apply to real estate investors, with the possible exception of depreciating a work-related vehicle based on mileage driven. Talk to your accountant before deciding how to depreciate your work vehicle.

Summary

Typically, real estate investors want to deduct as much as possible right now, for the current tax year, but Uncle Sam often forces them to slow down and depreciate expenses over time.

Use straight-line depreciation for rental properties, commercial properties, and capital improvements to them. Investors can also choose the depreciation method they want to use for purchases like appliances, electronic equipment, and work vehicles.

In some cases, investors can even argue that some property updates count as repairs or maintenance, rather than capital improvements. For example, replacing all your windows counts as a capital improvement, but what if you only replace a few windows a year?

When in doubt, speak with your accountant, and always remember the specter of depreciation recapture before getting too aggressive with your depreciation deductions!