What is Internal Rate of Return (IRR)?

REtipster does not provide tax, investment, or financial advice. Always seek the help of a licensed financial professional before taking action.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) Explained

The internal rate of return shows what the average return will be on an investment when the time value of money is factored into the equation.

Plain English: IRR is the speed of your payback turned into a percent per year.

Why it matters: Money you get earlier is worth more than the same money later, because you can put it to work sooner and earn more on it.

The easiest way to explain the time value of money is to give an example.

If you can get $20,000 today or the same $20,000 in six months, choose today. You could invest it right now and start earning. That is why IRR favors deals that return cash sooner. Earlier dollars are stronger dollars.

Money put to work now has a higher likelihood of earning more than money put to work in the future because of factors like compound interest.

IRR is a metric that provides insight into how profitable an investment is expected to be and properly accounts for the timing of cash flows.

How IRR Works in Practice

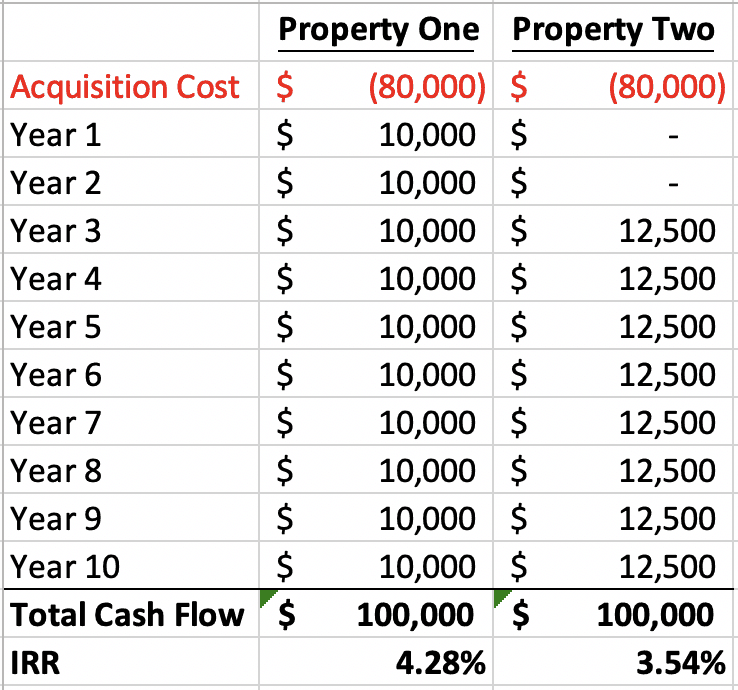

Imagine two properties with the same purchase price and the same total profit over a 10-year period.

- Property One pays $10,000 every year, starting immediately.

- Property Two pays nothing for two years during renovations, then pays $12,500 a year.

Even though Property Two pays more per year later, Property One has the higher IRR because it starts paying you back sooner. Earlier dollars are worth more. That is the whole idea behind IRR.

There is no promise you will actually earn that IRR. It is an implied rate based on your assumptions.

As illustrated by the example above, even though Property Two will generate more annual revenue after its renovations are complete, it won’t catch up with Property One until the very end of the 10-year period.

Both deals total $100,000, but Property One pays back sooner, so its IRR is higher (about 4.28% vs. 3.54%). It’s the same payback, but the faster payback wins.

Because of this, and due to the time value of money, Property One has a higher IRR and represents a better investment based on a 10-year time period.

IRR is an implied rate of return. There’s no guarantee an investor will achieve that return going forward, but the metric helps investors identify this kind of advantage within a property. (source)

How to Calculate the Internal Rate of Return

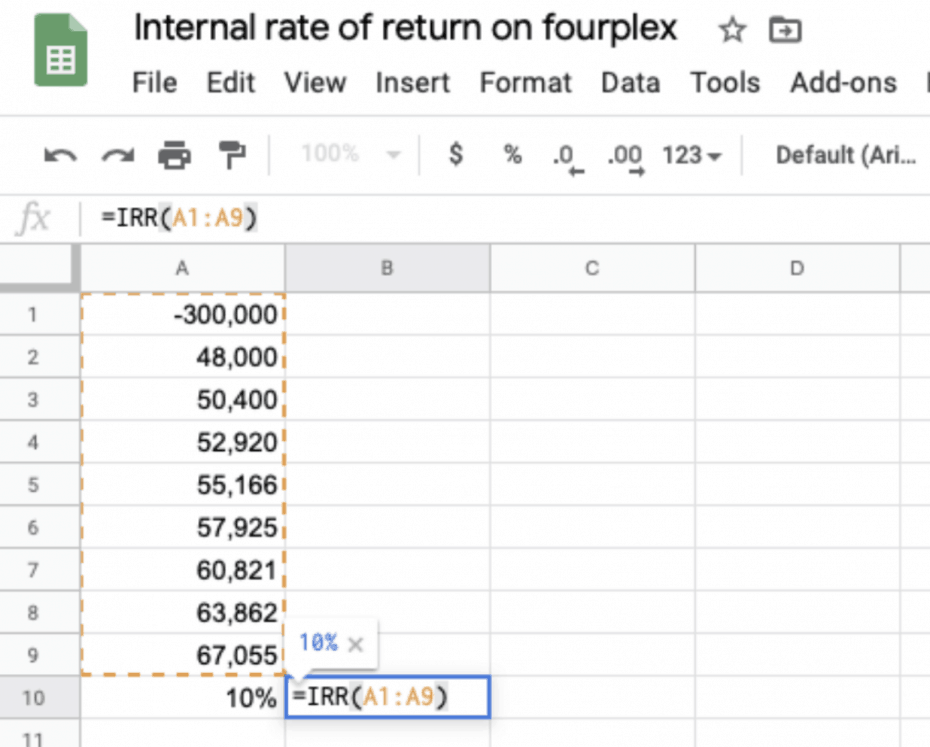

The internal rate of return formula is fairly complicated. Luckily, we have the use of tools like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets, which can make the calculation of IRR much easier.

To calculate the IRR using Excel or Google Sheets, start by entering the purchase price of the property in the first cell. In the example below, the investor paid $300,000 for the fourplex.

In cells A2 through however many years you are calculating for IRR, enter the cash flow.

Excel and Google Sheets calculate IRR for you. Use XIRR if dates are irregular.

In the final cell, enter the command =IRR(A1:An) where n is the last year in the period and Excel or Google Sheets does the rest.

Disadvantages to Using the Internal Rate of Return

IRR can be a very useful tool, but it has limits.

A high IRR doesn’t always mean a deal is the best one to pursue. For example, a small deal might have a high IRR but still make far less money in total than a larger deal with a slightly lower IRR. This is why it’s essential to consider net present value (NPV) and total dollars earned, rather than just the percentage return.

IRR also doesn’t measure risk, so you’ll only get a fair comparison if the properties have similar risk, holding periods, and leverage.

Earlier cash is worth more, which is why IRR favors faster payback.

Another issue is that traditional IRR assumes you can reinvest your cash flows at the same IRR rate, which is rarely realistic.

A more accurate approach is to use a modified version called MIRR, which lets you set a reinvestment rate that actually makes sense. On top of this, when cash flows change direction more than once (for example, you invest more money halfway through the project), IRR can sometimes produce multiple answers or no answer at all. In those cases, it’s better to use NPV, XIRR, or MIRR instead.

There are also a few common mistakes investors make when calculating IRR. One of the biggest is forgetting to include the sales proceeds from the property in the final year, which can drastically change the results.

Another mistake is mixing monthly and annual cash flows in the same analysis. You need to stick with one or the other.

Some people also think IRR is just the average of all their annual returns, but that’s not the case. It’s actually the single discount rate that makes the present value of your cash inflows equal the present value of your outflows. Errors in your assumptions can also throw off the calculation.

If your estimates for rent growth, vacancy, or expenses aren’t realistic, then your IRR won’t be either.

Finally, be cautious when comparing deals of vastly different lengths. A three-year flip and a fifteen-year hold are not directly comparable based on IRR alone. In those cases, it’s better to also run NPV or compare deals on the same time horizon.

FAQs About IRR

Is a higher IRR always better?

Usually, yes, if the deals have similar risk and hold period. A higher IRR with tiny total profit can still be worse than a slightly lower IRR with much larger dollars.

What is the difference between IRR and NPV?

IRR is the rate. NPV is the dollar value today after you plug in your own required return. Use both.

When should I use XIRR?

Use XIRR when your cash flows occur on actual calendar dates or at irregular intervals.

What about MIRR?

MIRR allows you to set a realistic reinvestment rate for your interim cash. It avoids the “reinvest at the IRR” assumption.

Reviewed by Brandon Renfro, Ph.D. and Kyle Kroeger