REtipster features products and services we find useful. If you buy something through the links below, we may receive a referral fee, which helps support our work. Learn more.

If you’re buying vacant land with plans to develop it, running into wetlands can be a pretty big challenge.

Wetlands are protected by the federal government (and usually by the state, too) because, even though they might seem useless to the average landowner, they actually serve a ton of important purposes—for people, fish, and wildlife.

This excerpt from the EPA sums it up pretty well…

Wetlands are important features in the landscape that provide numerous beneficial services for people and for fish and wildlife. Some of these services, or functions, include protecting and improving water quality, providing fish and wildlife habitats, storing floodwaters and maintaining surface water flow during dry periods.

Since wetlands are such a valuable natural resource, it makes sense that most government agencies try to preserve them whenever possible.

For the most part, if a property has wetlands, you won’t be able to build or develop in those areas without getting special permission from at least one (and often multiple) government authorities, and that permission won't be given unless you have a plan to mitigate the loss of those wetlands by buying ‘wetland credits,' which means that for every acre of wetlands you destroy, you need to create even more wetlands somewhere else nearby.

RELATED: Wetland Banks: The Untapped Goldmine of Real Estate Development

For land investors researching a property before buying, figuring out if wetlands are present can be tricky.

As the EPA explains:

Wetlands are often wet, but they’re not always wet year-round.

Some of the most important wetlands only get wet during certain seasons.

So, if wetlands aren’t always obvious and easy to spot, how can a land investor determine whether wetlands will impact their property?

Types of Wetlands

First off, it’s worth mentioning that wetlands can be pretty easy to spot in a lot of cases.

In the U.S., there are four main types of wetlands, and one of the most common is:

Marshes

Marshes are wetlands filled with soft-stemmed plants like grasses, rushes, or reeds. You’ll usually find them near lakes and streams because they act as a kind of transition zone between water and land.

There are actually different kinds of marshes, depending on where they’re located and how salty the water is. This also determines the types of plants and animals that can live there. (source)

Marshes can be found next to bodies of freshwater or saltwater along the coasts of major oceans and inland lakes. The water is typically only a few feet deep with mineral-rich and organic soil. (source)

Swamps

Swamps are usually dominated by trees and shrubs—sometimes called “forested wetlands.” They’re often found along rivers, where they depend on natural water level changes or on the edges of large lakes. Swamps are known for their slow-moving or stagnant waters and are usually found in low-lying areas. (source)

Historically, swamps and other wetlands have not been considered very valuable compared to fields, prairies, or woodlands. They've had a reputation for being “unproductive” land, mainly used for activities like hunting or trapping. (source)

Bogs

Bogs are freshwater wetlands with spongy peat deposits, evergreen trees and shrubs, and floors covered in thick moss—usually sphagnum moss. These wetlands often form in old glacial lakes and are most common in colder, temperate climates in the Northern Hemisphere. (source)

Unlike marshes, bogs get most of their water from precipitation rather than runoff or flooding. This gives their mossy floors fewer nutrients than you’d find in a marsh or swamp. There are different types of bogs, depending on their location and how they get their water. (source)

Fens

Fens are another type of freshwater wetland, but these are covered mostly in grasses, sedges, reeds, and wildflowers. You’ll often find them along lakes and rivers, where seasonal water level changes keep the soil wet. Unlike swamps, fens typically have fewer trees and shrubs, making them a bit more open and grassy. (source)

The problem with the EPA's definition of wetlands is that it leaves a lot of room for ambiguity.

Even though wetlands are often characterized by marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens, wetlands don't always have an observable presence of water on or near the surface.

Take the Florida Everglades, as one example.

Depending on the time of year, huge portions of this 734 square-mile wetland area are often dry.

Now, think about your backyard after a heavy rain. You might see some water pooling near your house—but that doesn’t mean you’re living on a wetland.

The point is that identifying wetlands isn’t as simple as just spotting surface water. It’s a lot more complex than that.

How to Identify the Presence of Wetlands

If you (or your future buyer) are concerned about wetlands on a property, there are two key terms you’ll need to understand:

- Wetland Identification – This is about figuring out whether an area qualifies as a wetland.

- Wetland Delineation – This involves mapping out the exact boundaries of the wetland—where it starts and ends.

If a landowner’s plans might impact a wetland’s function, both identification and delineation become really important. The catch? These processes can get pretty technical and complicated.

In most parts of the U.S., at least one (and often several) government agencies are involved in determining and regulating wetlands.

At the federal level, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) handle wetland delineation, with input from agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

In most states, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has the authority over the permitting process – as stated on the USACE website:

“Section 404 of the Clean Water Act requires that anyone interested in depositing dredged or fill material into “waters of the United States, including wetlands,” must receive authorization for such activities. The Corps has been assigned responsibility for administering the Section 404 permitting process. Activities in wetlands for which permits may be required include, but are not limited to:

- Placement of fill material.

- Ditching activities when the excavated material is sidecast.

- Levee and dike construction.

- Mechanized land clearing.

- Land leveling.

- Most road construction.

- Dam construction.

The final determination of whether an area is a wetland and whether the activity requires a permit must be made by the appropriate Corps District Office.”

In my state (Michigan), wetland development near “navigable waters” requires permits from both the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ). And here’s the kicker: these permits involve so much red tape that, unless you can prove there’s no other way to achieve your goal, the answer is often just “no.”

Because of all the hurdles involved, most land investors steer clear of wetland properties altogether. After all, who wants to buy land they can’t actually use?

This is why it’s so important to figure out if wetlands are present before closing the deal.

Online Tools to Help Identify Wetlands

The only way to be 100% sure about wetlands on a property is to bring in a wetlands consultant or have the right government agencies do an on-site identification and delineation.

But let’s be real—if you’re buying a property at a steep discount (at a price of less than $5K, for example) and need to close quickly, this “textbook solution” can feel completely out of reach.

Is there a faster and reliable way to get answers? Well… kind of.

If you’re looking to spot potential red flags without even leaving your computer, there’s a way to do some reconnaissance and get a clearer picture of the wetland situation on your property, which I explain in the video at the top of this blog post.

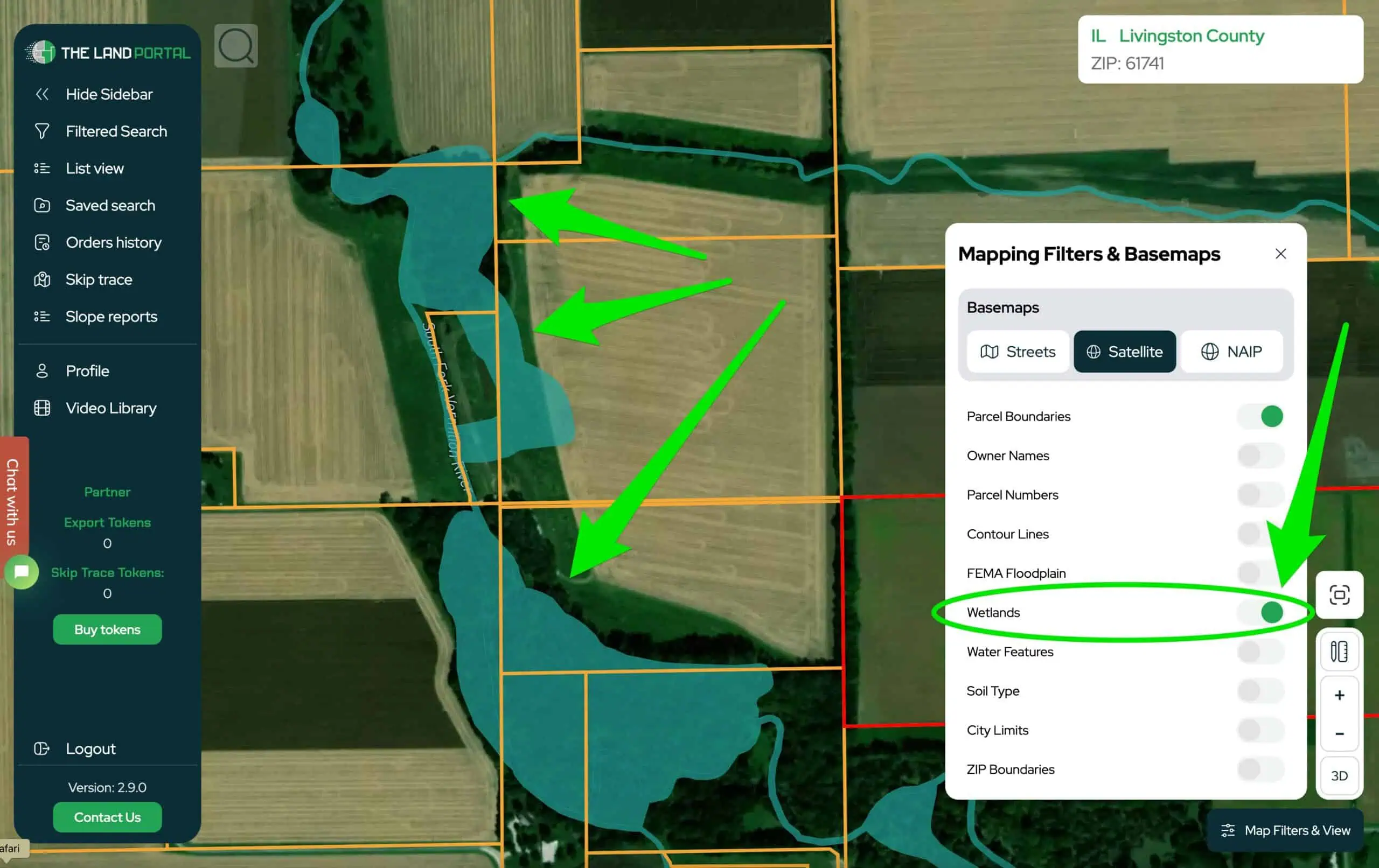

The easiest way is to use The Land Portal (subscription data service), or if you want to use the free method, you can use the Wetlands Mapper or download the KML file and view this same Wetlands Data on Google Earth.

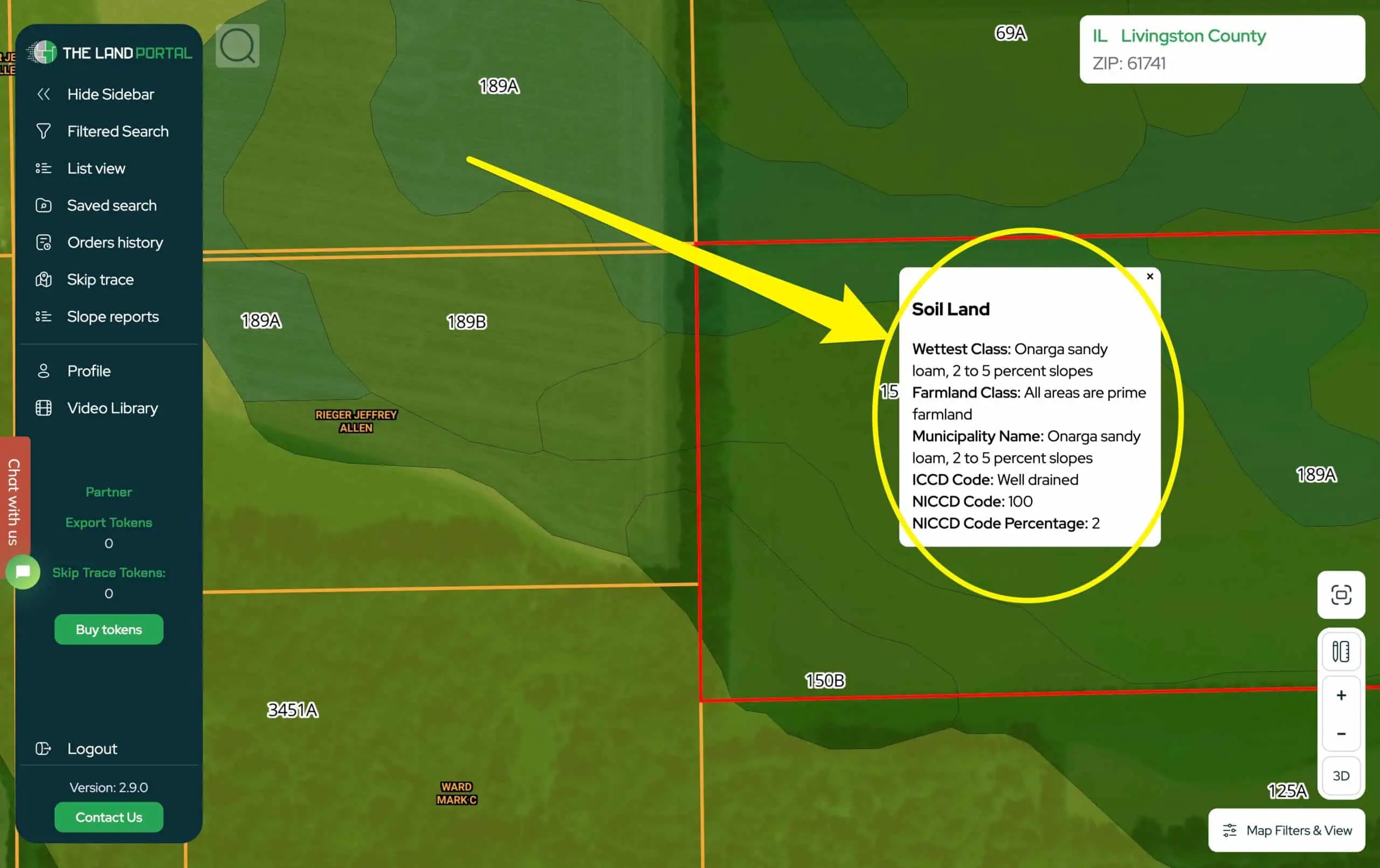

Since the wetlands mapper isn't always the most accurate measurement of the presence of wetlands, you can also refer to the USDA soil maps, which are also available in The Land Portal, or you can see them for free in the NRCS Web Soil Survey, which is compiled by the UC Davis Soil Resource Lab.

It’s important to remember that using tools like the Wetlands Mapper or the Web Soil Survey isn’t a substitute for hiring a wetlands consultant or having the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conduct an official delineation. These tools won’t give you a guaranteed answer—but they can provide a solid starting point if you’re looking for an educated guess.

If you’re serious about buying or developing a property, doing this preliminary research can save you time, money, and frustration down the road. Wetlands can complicate things, but with the right tools and a clear understanding of what you’re dealing with, you can make more informed decisions and avoid costly surprises.