REtipster does not provide tax, investment, or financial advice. Always seek the help of a licensed financial professional before taking action.

Owning real estate offers many significant tax advantages that other investments don’t.

Perhaps the most notable tax advantage is the ability to write off the cost of depreciation.

Depreciation is a “phantom expense” that the IRS allows real estate investors to deduct from their taxable income each year to account for the natural wear-and-tear that occurs to the physical improvements of a property.

The word “phantom” is often used because this expense doesn't have a tangible negative impact on the property owner's bank account. It's a paper loss that reduces the investor's taxable income and effectively reduces their annual tax obligation, even if there are no direct capital expenditures for the property in that tax year.

This ultimately means the real estate investor gets to keep more money and pay less to the government each year.

How Much Can Be Depreciated Each Year?

A building can be depreciated, but land cannot (i.e., buildings and equipment will eventually wear out and need to be replaced, but dirt doesn't).

Likewise, certain types of buildings and equipment will wear out faster than others, so to calculate this number correctly, it's important to understand a few key things:

- Property Value: What is the appropriate number to use for the property's beginning value?

- Land Value: What portion of the property's value is attributable to land rather than the building?

- Depreciation Timeline: How quickly can the value of the building, land improvements and equipment be depreciated and written off?

Doing this correctly will allow the property owner to save significant tax dollars each year (and when the property is eventually sold).

Doing this incorrectly will result in unnecessary tax expenses or penalties, so it's important to get this right!

RELATED: Finding the Right Accountant for Your Real Estate Business

How to Establish Property Value

As mentioned above, this process starts with establishing an appropriate value for the subject property… but when we're talking about real estate, “value” can be very subjective.

In the real estate industry, there are different ways to determine what a property may be worth, here are a few of the most common methods…

Appraised Value

When most properties are bought and sold, an appraisal is performed by a professional appraiser.

An appraisal is an unbiased assessment of a property's value, accompanied by supporting data to support the validity of the valuation. Appraisers will typically use the income approach, the sales comparison approach, and/or the cost approach to determine the most realistic value of a property.

Assessed Value

Every time a piece of real estate is bought and sold, the sale is reported to the local assessor so they know the change of ownership and the price paid for the property.

The assessor can use this data point, along with comparable property sales in the area to determine what the most realistic value of the property is.

Purchase Price

Since this is literally the price that was paid for the property, this could also be a reasonable number to use when determining the market value of the property and, ultimately, the depreciation amount.

So what's the right number to use?

When it comes to calculating eligible costs for depreciation, the baseline value always starts with what you PAID for the property (i.e. – the purchase price) and not what the value might be.

With that said, the issue of calculating the land value specifically (as opposed to the value of the buliding, land improvements or equipment) is another matter that needs to be evaluated separately.

How to Calculate Land vs. Building Value

Once we've established the baseline value (i.e. – acquisition price), the next step is to identify what portion of that number is attributable to the land.

Since this entire calculation is subject to the IRS's judgment, it's helpful to hear their input on how to do this:

“Since land cannot be depreciated, you need to allocate the original purchase price between land and building. You can use the property tax assessor's values to compute a ratio of the value of the land to the building.”

While the IRS doesn't explicitly state that the tax assessor's opinion of land value is the only option that can be used, based on this statement, the IRS seems to prefer this approach.

Using the Assessor's Opinion of Land Value

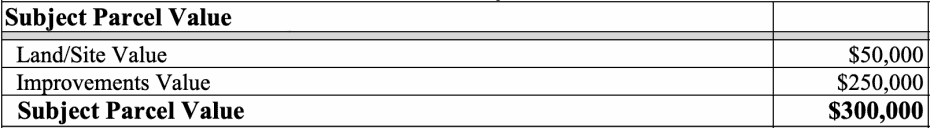

If we continue on this path of using the local assessor's opinion of the property's land value, we can use their percentages to come up with the right depreciable amount.

The IRS also offers the following example:

Ryan bought an office building for $100,000. [However,] The property tax statement shows:

- Improvements: $60,000 (75%)

- Land: $20,000 (25%)

- Total Value: $80,000 (100%)

In this example, Ryan's purchase price was different than the assessed value. However, he can use the same percentages as determined by the assessor and apply them to the original purchase price to determine how much can be depreciated.

In this case, he could multiply his purchase price of $100,000 by 25% to get a land value of $25,000.

The assessor's opinion of value can be found for free on most city or county websites that list property tax and ownership data. You can usually find these by doing a google search for something like:

CITY, STATE, PROPERTY TAX SEARCH

TOWNSHIP, STATE, PROPERTY TAXES

COUNTY, STATE, PROPERTY OWNER LOOKUP

If this data is easily accessible online (and usually is), these searches will probably find the website with this information.

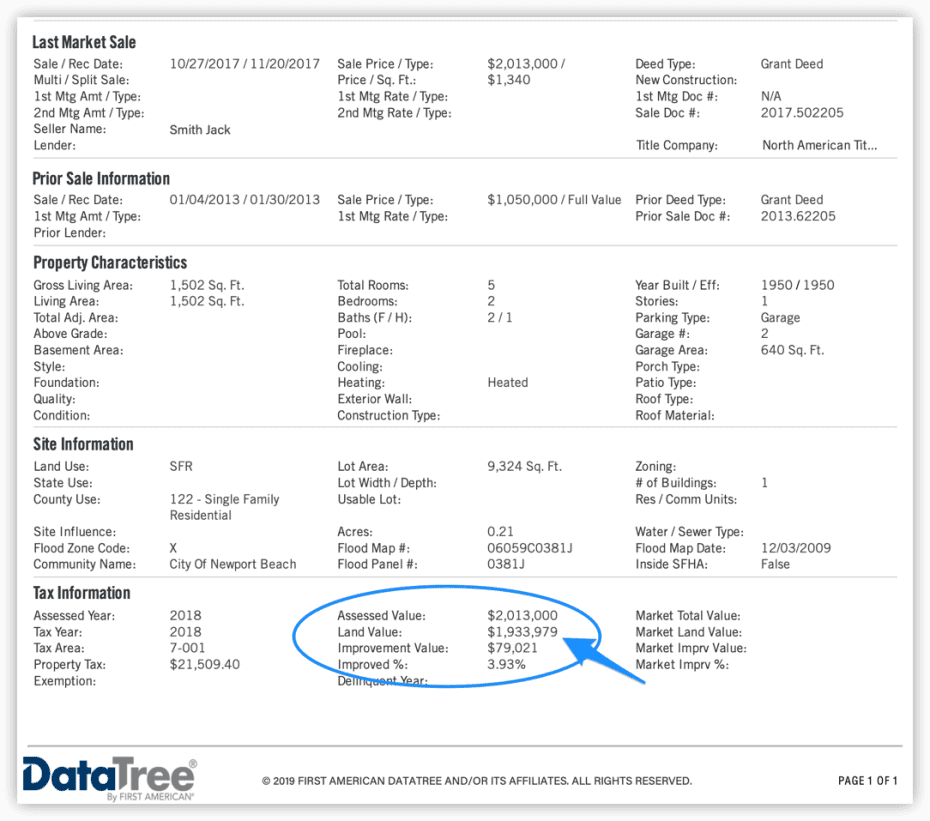

Alternatively, if you're a subscriber to a data service like DataTree, this same information can be found in their “Property Detail Reports” right here:

If you take this approach, it's pretty simple to find the assessor's opinion of your property's value AND what amounts they've designated toward land vs improvements.

Even though the assessor's opinion is probably the safest option (in the event of an IRS audit), it may not be the most accurate or advantageous for the taxpayer, and that's when it could be worthwhile to take another approach.

If another approach is sought, the tax preparer must be able to document and support their position (whichever one they choose) in case the IRS ever challenges these numbers.

Using the Appraiser's Opinion of Land Value

Most appraisals will spell out how much of the property's value is attributable to the land (sometimes referred to as “site value”) along with the replacement value of the improvements.

Since many appraisers look closer at the determining factors for a property's value, there's an argument to be made that this assessment of land value may be more appropriate to use (again, as long as the tax preparer documents this as their basis for determining the percentage allocable to land value vs. improvements).

Granted, there's always the possibility that the IRS could challenge this if they ever audit the taxpayer, but the important thing is that there was some reasonable basis for choosing these numbers in the first place.

Using Acquisition or Construction Cost to Determine Land Value

Aside from the assessor's and the appraiser's opinions of land value, it's also feasible for the tax preparer to use the actual purchase price as documented in the closing statement. This could be done if the closing documentation segregated what portion of the price was paid toward land, land improvements, buildings, and equipment.

A similar approach could be taken in the case of new construction, where it’s much easier to know exactly how much was paid for the vacant land, land improvements (i.e., sidewalks, landscaping, etc) construction of a building, and equipment. For example, this information can be tracked by following invoices and sworn statements from the general contractor.

When buying an existing structure on land, it is more difficult to come up with a reasonable basis for land value based on cost, and that's usually where the assessor's opinion of land value is an easy default option.

If the tax preparer decides to go another route, their decision should be based on supporting data and applied to the investor's tax return, based on the position that offers the greatest advantage to the taxpayer.

The IRS can audit the taxpayer at any point, so whatever rationale is chosen, this data should be well-documented and kept in the tax preparer's files so the taxpayer can support the number if needed.

Depreciation Timelines: Residential vs. Non-Residential Real Estate

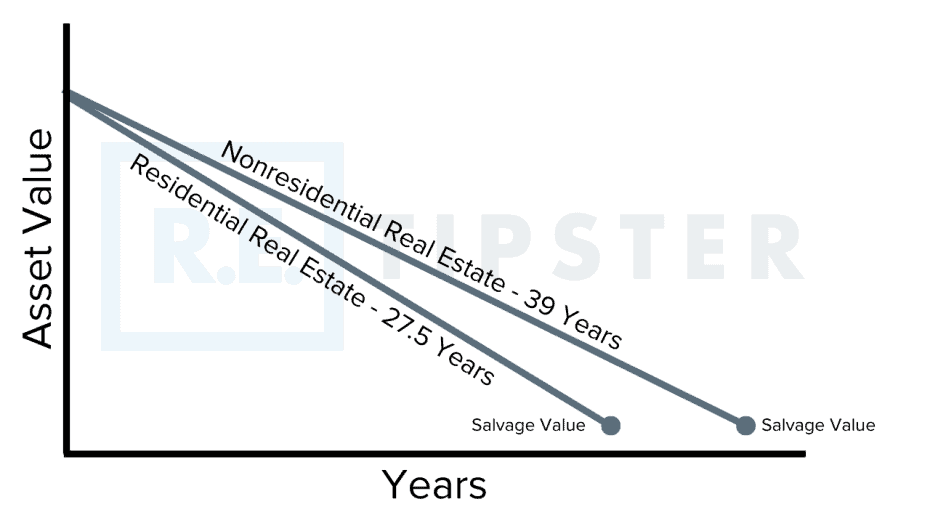

Once the land value is established, there are some notable differences in how quickly a property's improved value can be depreciated based on whether the property is “residential” or “non-residential” real estate.

In most cases, straight-line depreciation is applied to real estate. As the name suggests, straight-line depreciation requires that the original value of the improvements be spread out evenly and expensed over a set period in equal intervals.

At the time of this writing, residential real estate can be depreciated over 27.5 years, while non-residential (i.e., commercial, industrial) real estate can be depreciated over 39 years (source).

There may be portions of a piece of real estate that can be depreciated faster than that (Section 179 or bonus depreciation as an example) if they qualify, but the building itself will be straight-line over the appropriate number of years, based on whether it is residential or non-residential.

Residential vs. Nonresidential Real Estate

How exactly does the IRS classify a property as “Residential” or “Nonresidential”?

This IRS publication explains it very thoroughly, but these two excerpts are what you’ll want to pay attention to:

Residential rental property. This is any building or structure, such as a rental home (including a mobile home), if 80% or more of its gross rental income for the tax year is from dwelling units. A dwelling unit is a house or apartment used to provide living accommodations in a building or structure. It does not include a unit in a hotel, motel, or other establishment where more than half the units are used on a transient basis. If you occupy any part of the building or structure for personal use, its gross rental income includes the fair rental value of the part you occupy.

Nonresidential real property. This is section 1250 property, such as an office building, store, or warehouse, that is neither residential rental property nor property with a class life of less than 27.5 years.

In other words, if you own an investment property and 80% or more of its annual gross rental income is coming from dwelling units (i.e., people live in the property, including apartments, duplexes, etc.) then it’s considered residential.

A building with both residential and commercial (i.e., apartments on top and storefronts on the bottom) needs to pass the 80% test to be depreciated as residential property. Otherwise, it is classified as non-residential (you don’t prorate the costs of the property).

Equipment and Land Improvements

Another common scenario with commercial properties is when an improved property (i.e., land and building) is being purchased along with equipment (e.g., a building with a large crane that is difficult to move).

When equipment is tied to real estate like this, a buyer would likely want their purchase agreement to specify that they are buying both real estate and equipment and designate what portion of the purchase price is allocated to each category.

Equipment can be depreciated over a much shorter life than a building (typically 5 to 7 years, depending on the type of equipment and its useful lifespan), so if a property owner wants to take their depreciation deductions sooner, they would need to specify how much of the purchase price is being allocated towards the equipment.

Likewise, “land improvements” (e.g., sidewalks, fences, landscaping, parking lots, bridges, etc.) can also be depreciated faster (typically over 15 years) than the building itself. If the tax preparer is able to document what portions are allocable to these parts of the property, they could potentially take these depreciation deductions sooner as well.

Other Considerations

For some rental property acquisitions or pre-built or constructed buildings, it may be wise to consider a cost segregation study to break down the building components into smaller depreciable segments to get depreciation deductions sooner.

For example, if an 80-unit apartment complex is purchased with kitchen and laundry appliances included in each unit, the overall purchase price includes a lot of “equipment.”

If a careful inventory of these appliances is taken and thoroughly documented to support the value of those appliances, this could set aside a sizeable value to depreciate faster, thereby giving the property owner a larger tax break in the earlier five years of their ownership, rather than waiting the full 27.5 years to take full tax advantage of this depreciation expense.

As with any tax-related issue, deal-specific issues need to be evaluated by a licensed professional. A good accountant or financial consultant can play a big role in helping each investor extract the most benefit afforded by the tax code, and this kind of help can pay for itself many times over in tax savings.

Depreciation Formula and Calculator

Essentially, when put as an equation, the depreciation formula looks like this:

As the formula implies, the questions we need to answer are:

- What was the acquisition cost?

- What is the land (salvage) value?

- What are the years of useful life, according to the IRS?

Note that the 27.5 and 39-year depreciation calculations are typically based on a mid-month convention. In the first month, you acquire the property, you would get half (mid-month) of the first month's depreciation, not an entire month, and the same holds true in the month you dispose of the asset. For example, if you buy a residential property in December, you get 1/27.5/12months*.5 months. If you bought in November, it would be 1/27.5/12*1.5 months. This particular calculator does not account for the half (mid-month) convention.