What Is Estate?

REtipster does not provide legal advice. The information in this article can be impacted by many unique variables. Always consult with a qualified legal professional before taking action.

Shortcuts

- Estate describes a person’s total holdings and assets, especially in the context of the deceased or when a person files for bankruptcy.

- In many cases, an estate’s value is equivalent to the person’s net worth.

- Some assets may be exempted from the estate, such as life insurance policies with a beneficiary or the assets in a trust.

- Not all estates have to go through probate if the decedent has planned the estate well enough.

What Classifies Something as Estate?

An estate represents the sum of everything of value a person owns, including all types of property, assets, and other holdings. This term usually comes into play when discussing this person’s holdings when they pass away or file for bankruptcy.

All personal property and financial accounts fall under the umbrella of “estate.” Also, every single investment counts as part of the person’s estate. Company stocks and shares are a good example but may include mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, retirement accounts, and other bank products.

Moreover, personal belongings such as vehicles, appliances, jewelry, antique items, and collectibles like sports cards[1] are considered when determining the total value of an individual’s estate.

Likewise, tradable assets like commodities[2] and cryptocurrencies are counted in net worth calculations. Note that crypto may complicate estate planning because it is a new asset class [3].

Of course, precious metals like gold[4] can be sold to pay off debt and passed down to inheritors. Lastly, cash reserves (such as those kept in bank accounts) are also factored into the discussion of personal estate.

Estate Exemptions

While an estate touches all a person’s financial affairs, some assets are exempted from one’s holdings in an estate discussion.

For instance, life insurance policies with beneficiaries[5] are not subject to probate[6]. The death benefit from these insurance products is considered a non-probate asset[7].

Therefore, the authorities or the policy owner’s creditors cannot touch the proceeds from the life insurance.

The same goes for jointly held assets. Joint ownership rules can differ by state, so the survivorship rights of the living co-owners will depend on the jurisdiction[8].

What Is an Estate Used for?

An estate is useful when facing bankruptcy, settling debt, and distributing a deceased person’s wealth.

If one files for Chapter 7 Bankruptcy[9], this individual’s assets will be liquidated. The proceeds will usually go toward a portion of what one owes.

A bankrupt individual does not necessarily lose everything, though. State laws provide exemptions to preserve the assets one needs to maintain a household and a job[10]. For example, their home, car, retirement savings, and pensions are typically safe and excluded from bankruptcy estates.

RELATED: 6 Types of Bankruptcy and How They Impact YOU As a Borrower or Lender

On the other hand, upon death, a designated attorney or estate executor will attempt to zero out all of the decedent’s outstanding debts with the assets in the estate. The remainder is distributed to the survivors of the decedent (typically family members) and/or other qualified parties.

Estate Comparisons

An estate is liable to be confused with similar terms. Three of the commonly confused are described below.

Estate vs. Real Estate

Real estate and estate are similar terms but have different meanings.

Real estate means any form of real property—such as land, structures on and under it, and all ownership interest.

An estate is not limited to real estate in financial and legal contexts. Someone’s estate may include real estate but may also encompass other holdings. All types of real estate, including timeshares[11] under one’s name, are included in the estate.

Estate vs. Will

A will, short for last will and testament, is a legal document that provides instructions on distributing one’s assets upon death or who should take care of the decedent’s minor children, if any. It also names the executor, the personal representative responsible for carrying out the decedent’s final wishes.

Although it is not a requirement, a will is core to the effectiveness of a good estate plan. It can speed up the probate process, helping clarify how to proceed with estate distribution and eliminate disputes among the beneficiaries.

The probate court determines the validity of a will. The rules for verifying its authenticity vary from state to state.

In some jurisdictions, a valid will must have the signature of someone over 18 who understands what it is for and its contents. Plus, the will must be signed by at least two witnesses who are 18 years old or above.

In some states, the court may accept a handwritten will with no witnesses, provided that the individual who signed it and its author are proven to be the same person based on handwriting[12].

Without a will, the probate process becomes more complicated. First, the court needs to determine how the decedent would have wanted to distribute the estate. Then, to support their findings, they may gather evidence to identify the rightful beneficiaries of individual assets.

Some possessions are difficult to allocate by nature. Without a will, finalizing the decedent’s list of assets and naming the appropriate heirs could take months, if not years, to complete.

BY THE NUMBERS: Only 33% of Americans have prepared estate plans.

Source: CNBC

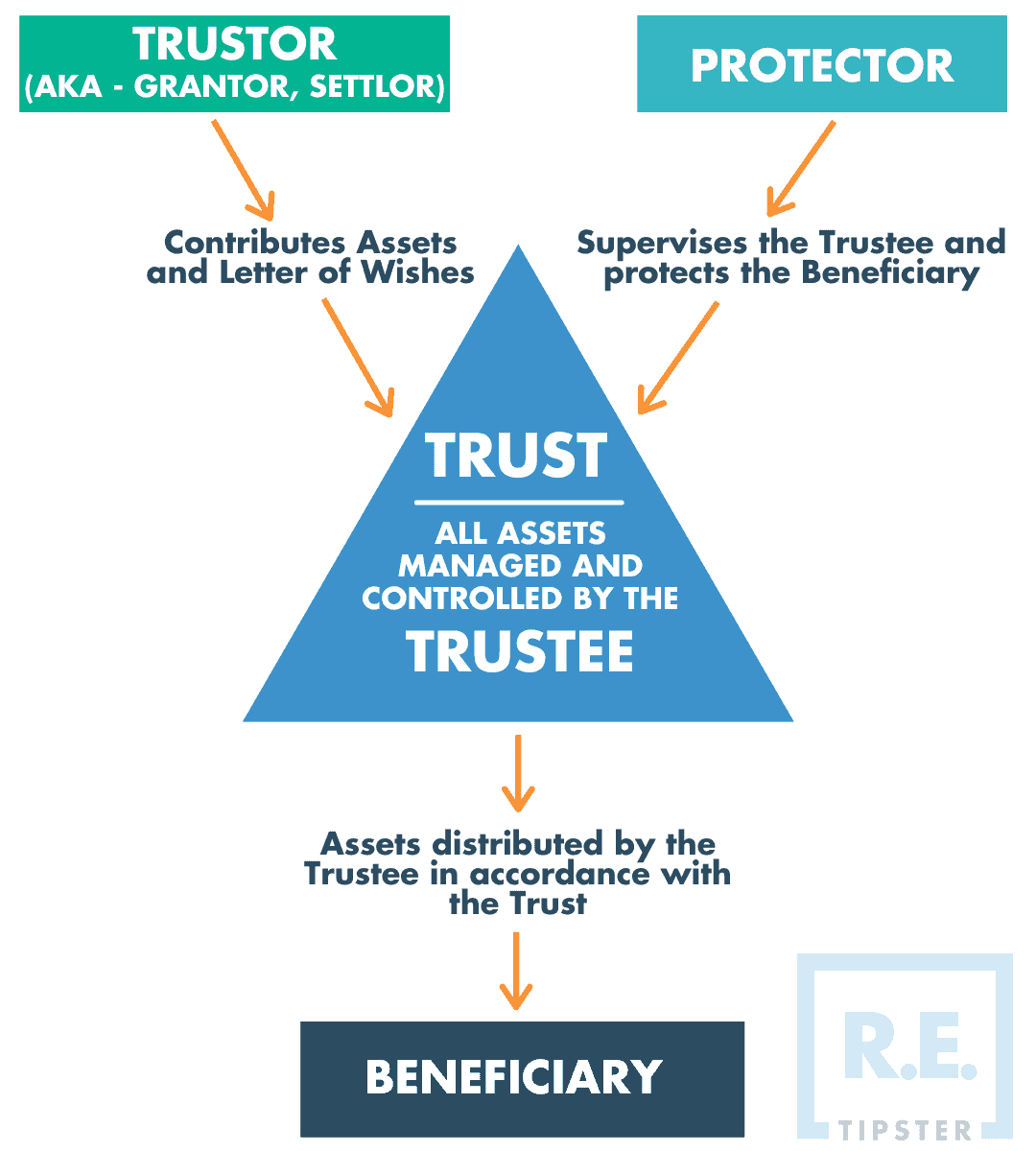

Estate vs. Trust

Like an estate, a trust consists of a person’s assets subject to distribution to specified beneficiaries.

Unlike an estate, which is nothing more than a collection of possessions, a trust is a legal entity that needs to be willfully set up by a person.

In most trust funds, the grantor (the trust’s creator) pools assets and hands them over to a trustee, the third party tasked with handling them. Then, the grantor names which assets in the trust will go to which beneficiaries under certain conditions. In other words, the beneficiaries cannot benefit from the trust’s assets without satisfying the trust’s requirements.

For example, the grantor can earmark funds from the trust for a beneficiary’s college tuition. Thus, the beneficiary cannot use the money for any other purpose, and the trustee will see to it that the cash is spent as intended.

Like a living will[13], a trust does not have to kick in only after the grantor dies. It is possible to create a living trust and have it take effect with or without the grantor’s death.

A living trust also typically survives the grantor, so it does not become part of their estate and thus continues to exist until its terms dictate or until it runs out of resources.

As with estates, trusts draw costs[14]. The trustee bills everything to the trust, including any payment to themselves for managing and overseeing it.

Does an Estate Have to Go to Probate?

An estate does not always have to go through probate, under certain circumstances and careful planning.

Using a revocable living trust is a common probate avoidance strategy. Accumulating non-probate assets is another.

Apart from convenience, not going through probate can help keep legal fees to a minimum, avoid estate tax, and protect the family’s privacy[15].

Sources

- Osacky, M. (2013.) Top Reasons Why Sports Cards and Memorabilia Collections Are Liquidated. Parade. Retrieved from https://parade.com/63624/michaelosacky/top-reasons-why-sports-cards-and-memorabilia-collections-are-liquidated/

- Hartill, R. (2022.) Commodities Trading: What Is It? The Motley Fool. Retrieved from https://www.fool.com/investing/how-to-invest/stocks/commodity-trading/

- Kerr, E. (2021.) What Holding Crypto Means for Your Estate Plan. U.S. News. Retrieved from https://money.usnews.com/money/personal-finance/family-finance/articles/what-holding-cryptocurrency-means-for-your-estate-plan

- Weston, L. (2021.) Dad didn’t trust banks. How to handle the hoard he left behind. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2021-06-16/gold-inheritance-cash-taxes

- Parrish, S. (2021.) Will It (My Home, My Life Insurance, Etc.) Be in My Estate? Kiplinger. Retrieved from https://www.kiplinger.com/retirement/estate-planning/603904/will-it-my-home-my-life-insurance-etc-be-in-my-estate

- American Bar Association. (n.d.) The Probate Process. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/real_property_trust_estate/resources/estate_planning/the_probate_process/

- Norris, P. (2019.) Estate vs. Non-Estate Assets. National Law Review. Retrieved from https://www.natlawreview.com/article/estate-vs-non-estate-assets

- Garber, J. (2022.) Understanding Ownership of Property. The Balance. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/how-property-is-titled-dictates-who-inherits-it-3505419

- Back, H. (2021.) What Is the Difference Between Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 Bankruptcy? Experian. Retrieved from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/bankruptcy-chapter-7-vs-chapter-13/

- O’Neill, C. (2016.) What Is a Bankruptcy Estate? Nolo. Retrieved from https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/bankruptcy-estate.html

- Weston, L. (2018.) How Not to Inherit Mom’s Timeshare. NerdWallet. Retrieved from https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/finance/inheriting-timeshares

- Finet, J. (2021.) The Most Important Differences Between Wills and Estate Planning. FindLaw. Retrieved from https://www.findlaw.com/estate/planning-an-estate/the-most-important-differences-between-wills-and-estate-planning.html

- Mayo Clinic. (2020.) Living wills and advance directives for medical decisions. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/living-wills/art-20046303

- Silva, D. (2022.) How much does it cost to set up a trust? Policygenius. Retrieved from https://www.policygenius.com/trusts/how-much-does-a-trust-cost

- Sember, B. (2022.) Do All Wills Need to Go Through Probate? LegalZoom. Retrieved from https://www.legalzoom.com/articles/do-all-wills-need-to-go-through-probate